By JOE SHARKEY

Michael Stravato for The New York Times

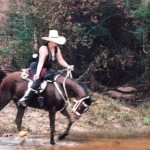

Cecilia Butler-French and DJB Foxfire on patrol at Bush Airport in Houston.

EASY,” I said, sounding way more calm than I felt. My horse’s vocabulary evidently did not include that particular word. We had pulled ahead of the pack at a flat-out gallop, flying over the grass and the muddy ditches on the perimeter of George Bush Intercontinental Airport near Houston. Trying to slow down, I shifted back in the saddle and squeezed the reins lightly, not wanting the horse’s head to rise to the point where he didn’t spot a ditch.

I cursed myself for forgetting the horse’s name, as this would have been a good time for intimate communication. We’d been galloping in a group of five for nearly two straight miles. The horses, mostly hot-blooded little Arabs, known for the ability to run like the blazes for miles on end, were not even panting. A half-mile ahead, I saw an intersection and a traffic light.

A spinning newspaper headline flashed through my head: “Scores Die in Collision of Airport Shuttle, Runaway Horse.”

I should probably explain here just what I was doing on horseback tearing around the grassy perimeters and splashing through the swampy backwoods within the secure boundaries of the Houston airport. I was out for a ride with a group of Houston Airport Rangers, a volunteer security force that patrols the barren perimeters and marshy woods of the 11,000-acre airport, under the supervision of the airport’s security office, looking for suspicious activity while enjoying the opportunity to ride 25 miles of airport trails and straightaways.

There are more than 800 certified Airport Rangers, volunteers who ride at all skill levels on various breeds of horses – including ones that stop a lot more willingly than the Arab I rode. My horse had been supplied by Darolyn Butler, who runs a nearby equestrian center and also races endurance horses around the world.

I’ll explain endurance riding in a minute. First let me say that I finally did get my Arab under control, though we were still moving at racetrack speed over bumpy ground. But then I lost my stirrups. Panic threatened, but fortunately I channeled the voice of Sheila Hunter, a superbly patient instructor who has basically taught me how not to get killed since I first started serious riding 10 years ago. “Heels down even if you lose your stirrups. You’ll get ’em back. Shoulders square. Hands quiet.”

I complied. Boots reclaimed stirrups. Shifting down to a smooth canter, the horse and I faded back into the little pack of riders. We all went into big posting trots, and then to a walk as the intersection came up. Among men, women and beasts on the ride, I was the only one breathing hard.

A fellow rider, Ceci Butler-French, Ms. Butler’s 22-year-old daughter, sidled up. “We saw you blow your stirrups, man. All we could do was watch how you handled it, and you handled it just fine,” she said. Suddenly I felt good, but pretty humble.

I learned about the unique Houston ranger program from a fellow rider not long ago. Intrigued by the idea that community involvement – in this case Houston’s large equestrian community – could intersect reliably with formal airport security, a couple of weeks ago I phoned David Poynor, who runs the program for the airport, and asked if I could join a patrol.

“Can you ride?” Mr. Poynor asked.

“I can generally keep one leg on either side of the horse,” I replied.

“Well, come on down, then,” he said.

For a little over a year now, the rangers, sometimes in small groups like the one I rode with, and sometimes in far bigger assemblies, have been patrolling the airport’s 35-mile perimeter during daylight, mostly along a new 25-mile trail network that meanders through dense oak, pine and sweet gum woods laced with creeks. But the trails also open onto long stretches of open land where horses can gallop, canter or just wander for miles near runways bustling with the landings and takeoffs of big airliners.

The program sprang from a unique conjunction of interests. Over the years, local horse people saw their once-expansive turf shrinking as a growing airport gobbled up landscape. After 9/11, the woodsy airport perimeter itself was closed to riders. At the same time, however, airport officials, like those at other domestic airports, were deeply concerned about the lightly secured perimeter of the complex. As at other airports, there was serious worry about such things as the threat of a terrorist climbing the chain-link fence to lurk in the woods and bring down a plane with a shoulder-held antiaircraft missile.

Ms. Butler is a former Miss Rodeo Oklahoma who had moved to Texas in the 1970’s. In 1974, she bought Cypress Trails, a small ranch and equestrian center beside a flood-prone creek near the airport. Cypress Trails supplies horses, mostly fleet-footed Arabs, for some rangers and, for a fee, for civilians who want ride along.

Ms. Butler said that when she left Oklahoma, “I was into quarter horse racing and cowgirl stuff like barrel racing.” But in 1981 she discovered endurance riding, an intensely competitive international sport that involves racing superbly conditioned horses, usually Arabs, over courses of 25, 50 or 100 miles in a single day.

From her ranch, along with the usual trail rides and lessons, she began offering endurance-training rides and managed an Endurance Race called the Houston Hustle, which became popular among top local equestrians, but which ended in 1996, as airport expansion and suburban development gobbled up trails.

The 2001 terrorist attacks caused domestic airports to clamp down on incursions. Logan Airport in Boston, for example, shooed away clammers who had been working the mud flats near a runway for generations. (A year later, the clammers, now equipped with cellphones and orange vests, were allowed back under an arrangement deputizing them to report suspicious activity.)

At the Houston airport, trails that had always been open to the public were suddenly off-limits. But after enlisting other local riders, including Rick Vacar, the director of the Houston Airport System, Ms. Butler led a campaign to reopen trails and even create new ones. At the center of the initiative was a newly invented volunteer security force, the mounted Airport Rangers.

This community involvement, with riding participants who had to obtain security clearances, met a genuine need to “help mitigate” potential exposure to terrorism on the airport perimeters, said Thomas B. Bartlett, the chief operating officer of the Houston airport. “The question was what can an airport do to secure its outer perimeter and adjacent property?” And Mr. Vacar said, “Just looking back at the history of Texas, what better way to patrol our perimeter than with horses?”

Greg Walker, the airport security manager, enthusiastically added his support, and the program began in December 2003, after new trails had been cut through the airport’s approximately 3,000 acres of woods.

“This is a serious security program,” said Mr. Poynor, who organized the rangers and the security clearance procedures they all go through. “Some of these woods are swampy, and you can’t actually get into them except on foot or on horseback.”

The program has a recreational element, of course. On any given day, several individual patrols of various sizes are likely to be riding at the airport, their leaders in contact with one another by cellphone. Mr. Poynor is working on a project to hire a core of 12 professional rangers to supervise the program.

Ms. Butler’s indefatigable Arabs are not the only equestrian breeds on the trails, by the way. Quarter horses, Saddlebreds and other easygoing cowboy horses are in fact in the majority.

So far, rangers have unearthed no terrorists, though airport officials say the presence of mounted patrols in isolated areas is a deterrent. Non-menacing intruders are often turned up and shown the way out. The occasional desperado has been tracked down in the woods. Deer wandering toward runways have been herded away.

Some local critics have called the program (which airport officials say cost less than $35,000 to set up) a boondoggle for the well-heeled equestrian set. Its supporters insist that the very presence of trained, observant riders perched high on horseback is an important and cheap contribution to security. But they also admit it’s a lot of fun.

After our intense ride – which covered more than 25 miles in less than three hours, a respectable endurance-riding pace – I told Ms. Butler truthfully that she had pushed me to the utter limit of my riding ability.

“Well, isn’t that the point?” she said.

Ranger Information

The public can join Airport Ranger rides as a ONE DAY guest of a ranger, or through the Cypress Trails Equestrian Center near the airport at 21415 Cypresswood Drive, Humble, Tex.; (281) 446-7232; or www.horseridingfun.com. Reservations are required, preferably at least two days ahead, particularly for weekends.

Cypress Trails also offers supervised off-airport adventure trail riding and dinner rides for all skill levels on a variety of horses, including paints, mustangs, appaloosas and Arabs. Basic rides are $30 for an hour, $50 for two hours and $65 for three hours.

Children are welcome. Tack and helmets are supplied.